The holidays got me. Now it is 2018, one day before David Bowie’s birthday and a lot has gone down since I last posted here. For one, I have been working with Slime mould! Physarum polycephalum to be exact. Here’s some fascinating Slime mould info from Wikipedia:

The holidays got me. Now it is 2018, one day before David Bowie’s birthday and a lot has gone down since I last posted here. For one, I have been working with Slime mould! Physarum polycephalum to be exact. Here’s some fascinating Slime mould info from Wikipedia:

Slime mold or slime mould is an informal name given to several kinds of unrelated eukaryotic organisms that can live freely as single cells, but can aggregate together to form multicellular reproductive structures. Slime molds were formerly classified as fungi but are no longer considered part of that kingdom.[1] Although not related to one another, they are still sometimes grouped for convenience within the paraphyletic group referred to as kingdom Protista.

More than 900 species of slime mold occur all over the world. Their common name refers to part of some of these organisms’ life cycles where they can appear as gelatinous “slime”. This is mostly seen with the myxogastria, which are the only macroscopic slime molds.[citation needed] Most slime molds are smaller than a few centimeters, but some species may reach sizes of up to several square meters and masses of up to 30 grams.[2]

Many slime molds, mainly the “cellular” slime molds, do not spend most of their time in this state. As long as food is abundant, these slime molds exist as single-celled organisms. When food is in short supply, many of these single-celled organisms will congregate and start moving as a single body. In this state they are sensitive to airborne chemicals and can detect food sources. They can readily change the shape and function of parts and may form stalks that produce fruiting bodies, releasing countless spores, light enough to be carried on the wind or hitch a ride on passing animals.[3]

They feed on microorganisms that live in any type of dead plant material. They contribute to the decomposition of dead vegetation, and feed on bacteria, yeasts, and fungi. For this reason, slime molds are usually found in soil, lawns, and on the forest floor, commonly on deciduous logs.

When a slime mold mass or mound is physically separated, the cells find their way back to re-unite. Studies on Physarum have even shown an ability to learn and predict periodic unfavorable conditions in laboratory experiments.[4] John Tyler Bonner, a professor of ecology known for his studies of slime molds, argues that they are “no more than a bag of amoebae encased in a thin slime sheath, yet they manage to have various behaviours that are equal to those of animals who possess muscles and nerves with ganglia – that is, simple brains.”[5]

Atsushi Tero of Hokkaido University grew the slime mold Physarum polycephalum in a flat wet dish, placing the mold in a central position representing Tokyo and oat flakes surrounding it corresponding to the locations of other major cities in the Greater Tokyo Area. As Physarum avoids bright light, light was used to simulate mountains, water and other obstacles in the dish. The mold first densely filled the space with plasmodia, and then thinned the network to focus on efficiently connected branches. The network strikingly resembled Tokyo’s rail system.[6]

I was introduced to Physarum polycephalum through InterAccess and doctoral candidate, Sarah Choukah from UofM.

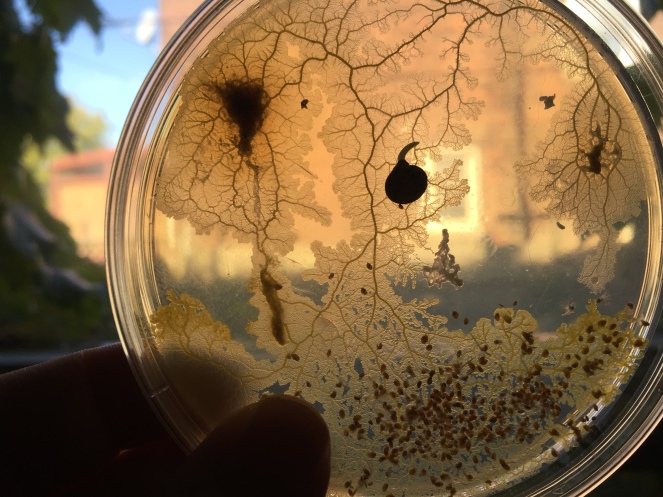

Sound, mapping, coloured agar, different energy sources for the Slimes (oat flakes are generally used) aside from simply creating (imho) beautiful patterns, are some of the experimentation my colleagues and I got up to with our ‘pet’ Slimes. First of all we had to learn how to ‘grow’ them in agar. My Slime was healthy and happy, up to a point. Some went into spore-phase while others died off.. I think? While others attempted to escape!

Meanwhile, I purchased a camera for my Raspberry Pi and have been gradually creating time-lapse videos of the Slimes’ adventures on 3 dimensional agar shapes so, stay tuned!

I linked to the following above, however it deserves to be shared in full here. This is Physarium music (perhaps even language?)

- “Introduction to the “Slime Molds””. University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- Jump up ^ Zhulidov, DA; Robarts, RD; Zhulidov, AV; et al. (2002). “Zinc accumulation by the slime mold Fuligo septica (L.) Wiggers in the former Soviet Union and North Korea”. Journal of Environment Quality. 31 (3): 1038–42. doi:10.2134/jeq2002.1038. PMID 12026071.

- Jump up ^ Rebecca Jacobson (April 5, 2012). “Slime Molds: No Brains, No Feet, No Problem”. PBS Newshour.

- Saigusa, Tetsu; Tero, Atsushi; Nakagaki, Toshiyuki; Kuramoto, Yoshiki (2008). “Amoebae Anticipate Periodic Events”. Physical Review Letters. 100 (1): 018101. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.018101. PMID 18232821. Lay summary – Discover Magazine (December 9, 2008).

- Jump up ^ MacPherson, Kitta (January 21, 2010). “The ‘sultan of slime’: Biologist continues to be fascinated by organisms after nearly 70 years of study”. Princeton University.

- Jump up ^ Tero, A.; Takagi, S.; Saigusa, T.; Ito, K.; Bebber, D. P.; Fricker, M. D.; Yumiki, K.; Kobayashi, R.; Nakagaki, T. (2010). “Rules for Biologically Inspired Adaptive Network Design”. Science. 327 (5964): 439–42. doi:10.1126/science.1177894. PMID 20093467. Lay summary – ScienceBlogs (January 21, 2010).